Recently there has been a slew of sensationalist articles about the now 16 Olympic athletes that have died since 2012. It seems like a lot - 16 people - but is it really? Based on the mortality rates of people aged between 25 and 44 in 1995 here, 192 people would be expected to die for every 100,000 per year. So, in fact, 16 people in 3 years is below the average.

Misuse of statistics may not seem like a terribly important thing to rally against but, when you think how many political decisions are taken backed by skewed information (WMD anyone?), you realize that lives could literally be saved if the general level of understanding of statistics were higher.

To take a example, the declaration by the WHO on the carcinogenic nature of processed meats has caused quite a lot of media attention recently, particularly in Spain, the home of jamón y chorizo. I was a bit surprised about how much attention it got as it seems we are always being told that such and such is bad for you (I'm pretty sure that bacon has always been on that list) even if, like in the case of margarine, we were once told with equal conviction that it was actually supposed to be good for us. So I thought I would try to see what recent research has caused the WHO to be so concerned.

Digging a little, it turns out that the IARC (International Agency for Research of Cancer) has recently confirmed the findings of the WHO publication Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. from 2002. Unfortunately, no other references were cited explicitly in the IARC's Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. In particular, the WHO document contains the following sentence:

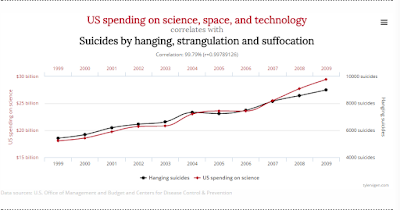

Let's suppose for a minute that there genuinely is a positive correlation between red meat consumption and risk of cancer. This is the classic case of causality not being the same as correlation. Maybe smokers tend to eat more red meat and also have a higher risk of developing cancer (although, admittedly, not colorectal cancer). What if we suspected that cancer sufferers were more likely to develop a craving for read meat? Then this study would appear to confirm our suspicion. These are perhaps facetious examples, but hardly a week goes by without some questionable claim on the BBC News website "based on scientific evidence". I particularly like this website, which goes out of its way to find spurious correlations, such as

The cause against Bad Science is not without its champions though, Ben Goldacre being the first to spring to mind with his book on the subject. It strikes me that kids today need to be much more equipped than we were to cut through the crap on the internet: there is just too much information available nowadays. Once something has been "re-tweeted" enough times it almost becomes fact by democracy. In my opinion there should be courses at school on how to determine the quality and validity of information - it's no longer a case of going to your local library and copying out the sentences from the only book you find. David Thorne says in his latest book

Misuse of statistics may not seem like a terribly important thing to rally against but, when you think how many political decisions are taken backed by skewed information (WMD anyone?), you realize that lives could literally be saved if the general level of understanding of statistics were higher.

To take a example, the declaration by the WHO on the carcinogenic nature of processed meats has caused quite a lot of media attention recently, particularly in Spain, the home of jamón y chorizo. I was a bit surprised about how much attention it got as it seems we are always being told that such and such is bad for you (I'm pretty sure that bacon has always been on that list) even if, like in the case of margarine, we were once told with equal conviction that it was actually supposed to be good for us. So I thought I would try to see what recent research has caused the WHO to be so concerned.

Digging a little, it turns out that the IARC (International Agency for Research of Cancer) has recently confirmed the findings of the WHO publication Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. from 2002. Unfortunately, no other references were cited explicitly in the IARC's Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. In particular, the WHO document contains the following sentence:

Factors which probably increase risk include high dietary intake of preserved meats, salt-preserved foods and salt, and very hot (thermally) drinks and foodNotice the word "probably" which I read in the linguistic sense, as opposed to the mathematical sense. Digging a little further, it appears that the academic paper on behind the "probably" is

Norat T et al. Meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a dose--response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. International Journal of Cancer, 2002, 98:241--256.I can't download the full paper for free (and I'm certainly not interested enough to spend my own money on it) but the abstract explains

The hypothesis that consumption of red and processed meat increases colorectal cancer risk is reassessed in a meta-analysis of articles published during 1973-99. The mean relative risk (RR) for the highest quantile of intake vs. the lowest was calculated and the RR per gram of intake was computed through log-linear models. Attributable fractions and preventable fractions for hypothetical reductions in red meat consumption in different geographical areas were derived using the RR log-linear estimates and prevalence of red meat consumption from FAO data and national dietary surveys. High intake of red meat, and particularly of processed meat, was associated with a moderate but significant increase in colorectal cancer risk. Average RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the highest quantile of consumption of red meat were 1.35 (CI: 1.21-1.51) and of processed meat, 1.31 (CI: 1.13-1.51). The RRs estimated by log-linear dose-response analysis were 1.24 (CI: 1.08-1.41) for an increase of 120 g/day of red meat and 1.36 (CI: 1.15-1.61) for 30 g/day of processed meat. Total meat consumption was not significantly associated with colorectal cancer risk. The risk fraction attributable to current levels of red meat intake was in the range of 10-25% in regions where red meat intake is high. If average red meat intake is reduced to 70 g/week in these regions, colorectal cancer risk would hypothetically decrease by 7-24%.So the recent furore is based on a the press picking up the IARC's confirmation of a publication by the WHO from 2002 which cites an academic paper, also from 2002, which is based on a collection of articles published between 1973 and 1999. I cannot claim to be an expert in Statistics but I do at least have a degree in Mathematics, albeit from more than half a lifetime ago. The numbers do appear to indicate a significant (in the mathematical sense) increase in colorectal cancer risk. What I find troubling, however, is that no single study in the period of 1973-1999 seems to have been "significant" enough for us to have reached this conclusion on its strengths alone; instead we have to rely on a so-called "meta analysis" which has to somehow homogenize, aggregate and summarize all the other results. Details about how the experiments were conducted, on what populations and with which controls etc, get lost in the wash. To be clear, I'm not saying that the conclusion is wrong, just pointing out how the information is collated and processed. Maybe processed information is just as bad for us as processed meat.

Let's suppose for a minute that there genuinely is a positive correlation between red meat consumption and risk of cancer. This is the classic case of causality not being the same as correlation. Maybe smokers tend to eat more red meat and also have a higher risk of developing cancer (although, admittedly, not colorectal cancer). What if we suspected that cancer sufferers were more likely to develop a craving for read meat? Then this study would appear to confirm our suspicion. These are perhaps facetious examples, but hardly a week goes by without some questionable claim on the BBC News website "based on scientific evidence". I particularly like this website, which goes out of its way to find spurious correlations, such as

|

| From http://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations |

|

| Excerpt from "Look Evelyn, Duck Dynasty Wiper Blades. We Should Get Them" |

No comments:

Post a Comment